Dive Brief:

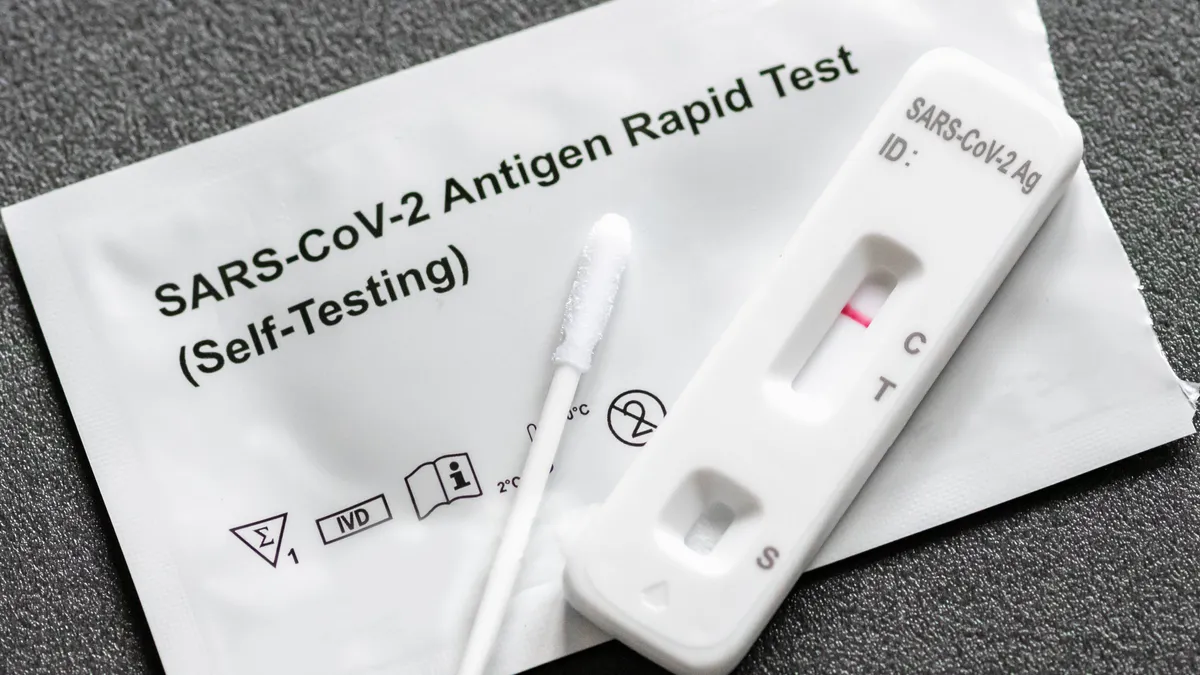

- Organizations’ efforts to keep the workplace safe as they carry out return-to-office policies could run afoul of a little-used federal law if they try to get COVID-19 test results from employees and their family members.

- In a settlement with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a company in Florida last week agreed to provide back pay, restore leave time and cover damages to employees that it sought test results from before they could return to the office.

- The company’s practice violates the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act (GINA), passed in 2008, which prohibits the collection of genetic information from employees and their family members and also the collection of family members’ medical history. “This resolution illustrates the need for employers to review their COVID-19 policies and practices … to ensure that they are in compliance with federal EEO laws,” Evangeline Hawthorne, an EEOC field office director, said in announcing the settlement.

Dive Insight:

Charges brought under the law are relatively rare, typically comprising less than 1% of the EEOC’s annual caseload, according to agency data.

But the settlement reinforces that GINA can be applied to practices that aren’t directly related to genetic matters because of its prohibition on collecting family medical history.

“GINA defines ‘genetic information’ to include the manifestation of a disease or disorder in an employee’s family members,” the EEOC says.

EEOC says it’s permissible to ask employees, before they can return to the office, if they’ve come in contact with anyone who’s tested positive or if they have COVID-like symptoms. But employers can’t ask about the COVID status of family members.

The prohibition doesn’t apply to employees who are trying to get time off under the Family Medical Leave Act. There’s also nothing prohibiting organizations from collecting family medical history if it came from publicly available sources.

ADA applies, too

Although the settlement shines a spotlight on GINA, general counsel need to keep their eye on the Americans with Disabilities Act as well as their organization decides what to do about bringing employees back. That law more broadly prohibits discrimination based on medical history. But there’s an important distinction between the two.

ADA requires employees to show harm if they file a claim; GINA doesn’t.

That makes GINA functionally an employee privacy statute, Jessica Roberts, a University of Houston professor, says in a Bloomberg Law report.