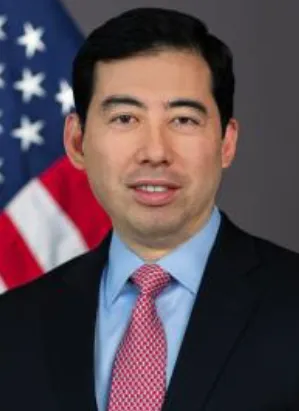

A handful of changes in how the Securities and Exchange Commission weighs in on shareholder proposals can help lessen the chance a company’s annual meeting devolves into a social-issue battleground, Commissioner Mark Uyeda told the Society for Corporate Governance.

Shareholders submitted almost 1,000 proposals to companies this year, up almost 20% from two years ago, and many of those were for social-issue matters that didn’t necessarily have much to do with the company’s core business—and few of them ended up passing.

Only 3% of proposals relating to environmental and social issues that made it onto the company’s annual meeting agenda passed, even as the number of these types of proposals that went to a vote increased by 125% over 2021, according to data Uyeda shared.

The large number of measures combined with their low passage rate translates into a lot of time, effort and resources going into matters that aren’t necessarily central to many company’s core business, Uyeda said.

“Shareholder meetings were not intended under state corporate laws to be political battlegrounds or debating societies,” he told the group, whose annual meeting was June 21-23. “Already, some asset managers have expressed concern that the influx of shareholder proposals are not resulting in a corresponding increase in enterprise value.”

Federal facilitator

The SEC’s role in the proposals is mainly to help ensure shareholders have an appropriate process for getting their proposals heard, Uyeda said. It’s not to supplant the company’s own process that’s created under the rules of the state in which it’s incorporated.

“A company should have the right to adopt, in its governing documents, requirements for shareholder proposals that differ from those set forth in rule 14a-8,” said Uyeda, referring to the 1942 SEC rule that governs the agency’s role in facilitating shareholder proposals. “If this were not the case, then the federal securities law will have supplanted state law on the issue of whether a shareholder can add a proposal to the meeting agenda.”

Many high-profile companies have come under the spotlight in recent years for taking stands on social issues, and shareholder proposals are seen as a big driver of that, according to data compiled by Proxy Preview. That’s particularly the case on climate change.

“Investors [are] calling for executives and corporate boards to set targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions,” says an NPR report on the environmental aspect of the trend.

Core-business proposals

Uyeda said there are steps the SEC can take to help bring shareholder proposals back into alignment with core company business and away from social activism.

One is to create a single standard for evaluating social policy issues. Proposals are currently looked at under a pair of standards in Rule 14a-8 that have grown in complexity over time.

“Many practitioners in the 14a-8 bar probably agree that each paragraph’s standard is needlessly complicated on its own,” he said.

He recommended doing for social issues what the rule does for risk issues: evaluate them under just one standard, and make that standard subject to materiality.

“The standard could be similar to that for risk factor disclosure, where the Commission requires disclosure of material risks and discourages inclusion of ‘risks that could apply generically to any [company],’” he said.

Put another way, if a social issue impacts all companies and doesn’t necessarily single out a company because of its business model, there are grounds for excluding that issue from a vote.

Another change is to let companies set their own standards separate from the Rule 14a-8 standard as long as their standards adhere to state law. If there appears to be a conflict between the standards and the law, the company can deal with it in court.

“Any disagreement between the proponent [of the shareholder proposal] and the company should be treated like any other dispute over an interpretation of a company’s governing documents and resolved in state court,” he said.

The SEC’s role, he said, should come into play only when the company doesn’t set its own standards.

“Rule 14a-8’s procedural bases … should be viewed as default standards that apply only if companies decline to establish their own standards in their governing documents,” he said.

A third recommendation touches on SEC staff process issues that add unnecessary complexity to the agency’s role. Among other things, SEC staff attorneys are being asked to weigh in on how a proposal intersects with legal issues, and that’s something they should only do in connection with federal securities law, because that’s their area of expertise.

“The staff is not expected to have expertise with respect to the issues of state law or foreign law,” he said.

The recommendations, he said, are intended to redirect shareholder proposals back to the core interest of companies.

“The Commission’s mission is to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation,” he said. “The Commission will not succeed in that mission if it does nothing to prevent value-eroding shareholder proposals from being part of the annual meeting process.”